Coming to Terms With Germany’s Colonial Misadventures

written by Patrick Kornegay Jr., University of Connecticut European Horizons Alumnus

In the aftermath of George Floyd’s murder and the racial unrest that followed, America has had to come to terms with its racial past, be it issues with flags, statues, current army installations that all have links to the Confederacy. Although one of America’s closest allies, Germany, has been an exemplar in its own dealing with its past (termed die Vergangenheitsbewältigung), it should follow American citizen’s example of coming to terms with its racial past. Germany, with regards to its colonial/imperial misadventures, still struggles with to this day.

From 1871–1918, Germany was an empire under the rule of the Kaisers after Germany defeated France in the Franco-Prussian War, allowing Germany to unify through the leadership of Chancellor Otto von Bismarck. Once Germany became a recognized state, it immediately wanted to be at the table with other great European powers, and one way to do that was to acquire colonial possessions. The German Empire controlled vast territories in Africa and Asia (3rd largest in terms of territory behind Great Britain and France), spanning from Kamerun (Cameroon), Togoland (Togo), German East Africa (Rwanda, Burundi, Tanzania), German Southwest Africa (Namibia) to German New Guinea (encompassing much of Papua New Guinea and a vast swath of territory in the south Pacific), German Samoa, and treaty ports in China (Tsingtao, Chefoo, and Jiaozhou Bay).

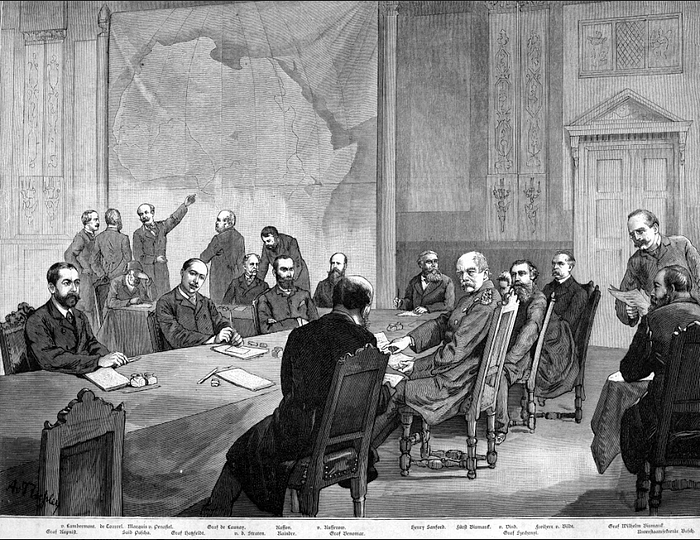

For Africa, much of the territories were drawn out during the “Scramble for Africa”. This was a land grab orchestrated by rival European powers in the late 19th century in the era of great power competition. This scramble was facilitated by Chancellor Bismarck at the Berlin Conference of 1884 (titled “Kongokonferenz”), and this was where, “the boundaries drawn during that conference, which were determined on the basis of the economic and military interests of European statesmen, remain valid to today” (Ayim 21). Much of these territories were taken for raw materials (rubber, palm oil, sisal, minerals, etc.). Involvement by the German colonial government differed from colony to colony, where railroads, missions, and military garrisons were sent throughout the empire, and the ultimate desire was to, “govern as cheaply as possible, consistent with limited economic aims, and if possible, govern indirectly through those organized structures with a stake in development, whether white or black” (Hammerstein 89).

Indigenous people in many respects did not take to being ruled from an alien power and rebelled, one of the most well-known being the Maji-Maji Rebellion in German-East Africa (1905–07), which was conducted by several different groups of people, revolted were able to control much of the country before being defeated by the Germans, resulting in tens of thousands of deaths. “The cement that held Maji-Maji together and gave it its peculiar character was magic and popular religion. The rebellion was organized by itinerant religious figures or ‘medicine men’ who developed a magical ideology of resistance to appeal to different peoples. Maji-Maji itself refers to an incantation that was supposed to turn German bullets into water” (Hammerstein 107).

The Maji-Maji Rebellion is important in today’s story because several streets in Berlin are being renamed due to colonial leader’s connections. One of them was Carl Peters who helped found the East African colony and was Germany’s, “most famous colonialist, but his use of violence in native relations, due apparently to a sadistic streak in his nature, was clearly excessive” (Hammerstein 95). The effort would go to change the names of colonial advocates and leaders to ones honoring those who fought and rebelled against Germany’s colonialist aggression, one street possibly going to honor this struggle. Many of the streets that were named after colonial leaders were erected during the Third Reich as a way to get the German people interested in restoring their lost territories. Another street name that has come under review and changed came as a direct result of the current racial tensions from the US. This street is named Mohrenstraße (Street of the Moors). “Berlin’s public transport company BVG said on Saturday that completing the renaming of a city centre metro station with a name based on a derogatory word for black people will take until the end of the year” (Eckert 2020). This is just a further example of the lengths the country is going to come to terms with its darkened colonial past.

When talking about German colonialism, the genocide in South-West Africa (Namibia) must be mentioned. This was the very first genocide of the 20th century and would be a model for how future ones would be carried out, and indeed a line can be drawn here to the Holocaust as well in terms of its brutality. This came about as a result of a rebellion in Namibia (lead by the Herero and Nama peoples) and the German forces there would push the fighters and their families to the desert, where ~100,000 died from exposure and dehydration, and many more being placed in concentration camps. This was disastrous for the Herero people especially because to them, the land meant everything and connected them with their past, “Each Herero family has a fire in their backyard. The Herero believed that this fire contains the souls of their ancestors. Because of this, they believe that the fire must be kept constantly burning or else their ancestors would be destroyed … But that fire went out when his grandfather was forced out of his home, and when that fire went out his ancestors died. He believed that his ancestors, all of them, were murdered because the fire went out. Can you imagine that? His entire lineage, all of that history that was remembered and remembered and remembered until it was killed, and then it was forgotten” (Drury 34,90). This example goes to highlight just how much Germany displaced and exterminated a whole race of people and is indicative of how that shows a linear path from the Namibian desert to the concentration camps. “The genocide of Herero and Nama represents a still more enhanced form, a genocidal war of conquest and pacification where large contingents of troops under a single supreme command are brought into action over an extended period. The beginnings of a bureaucratic form of extermination are also already present in the camps. This form of mass murder presupposes the existence of a modern centralized state” (Hammerstein 60).

This is important in today’s terms because Germany still has complications over the role its citizens played in the genocide. An official German apology for the horrors of its colonial rule remains to be seen — even though Germany and Namibia have been negotiating at government level since 2015” (Deutsche Welle 2019). There are talks of reparations and even a court suit is going to New York City to sue the German government. One suggestion is to even go the route of former West German chancellor Willy Brandt who knelt in Poland to help atone for his country’s atrocities committed there in World War II. These are different suggestions for ways to come to terms with the atrocities committed by the Germans here and is long overdue. Another example of restitutions is the return of skull and bones that were taken from Namibia following the Herero genocide, “Foreshadowing the Nazis, the skulls and bones were brought to Germany for pseudo-scientific experiments seeking to demonstrate the racial superiority of white Europeans” (Pape 2018). This episode is just another example of Germany having to deal with its thinly veiled colonial past and discussions are still being done with regards to compensation.

Germany’s colonial possessions were also linchpin issues with the genesis of both world wars. The issue of balance of power was a major spark that brought about the start of WWI. Once the war ended, all of Germany’s colonies were divided up among other colonial powers as protectorates and mandates. The return of these colonies to Germany was even up to debate during appeasement in the 1930s, “Churchill made his last suggestion for buying off the Nazis with the restoration of their colonies — and only if all the rest of the Great War’s victorious allies joined in — on 21 December 1937. ‘It would have to be part of a general settlement,’ he said, which would involve Hitler disarming to some extent and giving up any future territorial demands” (Roberts 421). This would be rejected and would not be carried out as Hitler continued to grab territory in Europe and spark World War II when he invaded Poland in 1939.

This chapter of German history is one that must be told and elaborates on why Germany acted the way it did for much of the 20th century, and if a change is to be made, similar to discussions about Confederate monuments and police brutality in the US, the core root of the issue must be investigated and discussed. More must be done to rectify the injustices that were committed and to right the wrongs that were done to those that were oppressed, that are crying out, and still feeling the aftereffects of those deeds to this day.

Patrick Kornegay Jr. is a recent graduate from the University of Connecticut. He has spent time at conferences and founded an EH chapter at UConn. He is an incoming fellow for the Congress Bundestag Youth Exchange for Young Professionals (CBYX) and is planning on living and interning in Germany next year. He is applying for graduate schools in both D.C. and Europe. He is extremely interested in geopolitics and specifically the German-American relationship. He is hoping to one day serve in a role that contributes to that relationship. He is humbled and thankful for his time being involved with European Horizons and being inspired to want to be a part of something bigger than himself.

Works Cited

Ayim, May, et al. Showing Our Colors: Afro-German Women Speak Out. University of Massachusetts Press, 1992.

Deutsche Welle. “Genocide: Namibia Still Waiting for a German Apology: DW: 16.09.2019.” DW.COM,2019, www.dw.com/en/genocide-namibia-still-waiting-for-a-german-apology/a-50445209.

Drury, Jackie Sibblies. We Are Proud to Present: a Presentation about the Herero of Namibia, Formerly Known as Southwest Africa, from the German Sudwestafrika, between the Years 1884–1915. Bloomsbury, 2014.

Eckert, Vera. “Berlin Metro to Change ‘Racist’ Station Name by End of Year.” The Independent, Independent Digital News and Media, 4 July 2020, www.independent.co.uk/news/world/europe/berlin-metro-mohrenstrasse-rename-racist-station-a9601641.html.

“List of Former German Colonies.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 15 June 2020, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_former_German_colonies.

Pape, Elise. Germany’s Confrontation with Its Colonial History: Are There Lessons from Grappling with the Nazi Past? American Institute for Contemporary German Studies — Johns Hopkins University, 2019, www.aicgs.org/2018/10/germanys-confrontation-with-its-colonial-history-are-there-lessons-from-grappling-with-the-nazi-past/.

Roberts, Andrew. Churchill: Walking with Destiny. Viking, 2018.

Von Hammerstein, Katharina. Germans in Africa, Blacks in German-Speaking Countries: Colonial and Postcolonial Perspectives. XanEdu Publishing, 2019.